Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Underlying Factors Behind Growth of Structured and Illiquid Assets

Publication date May. 28, 2024

Summary

The low interest rate environment has persisted since the 2008 global financial crisis, leading to significant growth in the market for structured and illiquid assets, often characterized as “medium risk, medium return”. These assets offer relatively high returns when market conditions are favorable, but involve complex structures and inherent risks. Investors unfamiliar with structured and illiquid assets could be exposed to cognitive biases that induce them to underestimate the associated risk and perceive these assets as being safer than they actually are. Consequently, these investors may allocate an excessive amount of funds into such assets, potentially suffering significant losses when market conditions deteriorate.

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, the prolonged low interest rate environment has led to a significant increase in domestic investment in structured and illiquid assets. For example, the outstanding balance of ELS (equity linked securities) and DLS (derivatives linked securities)1) more than quadrupled from KRW 22 trillion at the end of 2010 to KRW 94 trillion by the end of 2023. Similarly, investments in real estate funds, a typical illiquid asset class, surged from KRW 14 trillion to an impressive KRW 170 trillion over the same period. This indicates that investors, frustrated with low market interest rates, have gravitated toward products that claim to offer ‘medium risk, medium return’ in search of excess returns. Structured and illiquid assets yield relatively high returns under favorable market conditions. However, they differ significantly from traditional assets due to their structural complexity and inherent risks. The recent Hong Kong ELS crisis and the subsequent losses in offshore real estate funds have highlighted these limitations. Against this backdrop, this article explores the underlying factors behind the preference for structured and illiquid assets, with a particular focus on how cognitive biases affect investor decision-making.

Biases in structured asset investing: A focus on ELS

ELS, introduced in Korea in 2003, represents a typical structured asset class that drew significant attention as a “financial product innovation”. It has contributed to broadening investment choices for the general public. For example, step-down ELS involves a profit structure similar to that of selling a put option, providing investors with option premiums. These option premiums can be an attractive choice for investors seeking excess returns above market interest rates.2) Before the introduction of ELS, these option premiums were typically reserved for financial institutions. For investors to directly sell options from their accounts, they needed to maintain sufficient margin and satisfy regulatory requirements set by financial authorities or exchanges, as well as the strict trading conditions imposed by individual securities firms. In particular, the “deep out of the money option with maturities longer than six months”, included in step-down ELS, could only be traded as an over-the-counter product, making it accessible exclusively to financial institutions with adequate creditworthiness, despite its relatively low risk compared to typical put options. The emergence of ELS has addressed these limitations and expanded retail investors’ access to over-the-counter derivatives. In addition, despite the inclusion of derivatives, ELS has enhanced convenience for retail investors by limiting potential losses to 100% and allowing for small investments. Consequently, ELS has enabled retail investors with relatively low risk appetite, who may be hesitant to directly participate in the stock market, to benefit from investing in ELS while managing a relatively low level of market risk. In other words, ELS can be seen as a product that fulfills one of the fundamental functions of finance: “risk diversification”.

Despite these positive effects, ELS comes with its own drawback of complicating the understanding of inherent risks for ordinary investors. In the derivatives market, there is always an investor taking an opposite position, and selling a put option involves a transaction conducted in the opposite direction of put option buyers. The counterparty buying the put option would not pay for an event that has no possibility of occurring.3) Although ELS is considered to entail a relatively low level of risk, it inevitably carries risk to some extent. Furthermore, the risk associated with put options stands in stark contrast to the risk commonly faced by ordinary investors in the stock market. Specifically, while the frequency of losses in ELS is significantly lower than in stocks, the value of the expected loss is substantially large once it occurs (Kang, 2016).4) This risk is not readily recognized by ordinary investors, and as a result, they may opt for a product that hardly aligns with their risk appetite and suffer significant losses.

Investors are susceptible to cognitive biases as they struggle to fully grasp the risk inherent in ELS investing. For example, in the case of step-down ELS, investors can see the coupon or rate of return they can earn if certain conditions are met. In a low interest rate environment, the ELS coupon rate may be perceived as being significantly higher than market rates, which induces investors to overreact and recognize ELS as a more attractive investment than it really is. When the market rate stands at one percent, an ELS coupon rate of five percent may seem quite appealing. In this situation, investors tend to overestimate the prominent features of a financial product such as its coupon rate, while undervaluing less conspicuous features like the risk of loss. This tendency is well demonstrated by Bordalo et al. (2012, 2016) who elucidate this phenomenon by applying the “Salience Theory”. For this reason, investors show a propensity to allocate excessive investments in ELS products. According to Célérier & Vallée (2017), amid a low interest rate environment, this salience effect significantly contributed to the growth of the European structured asset market, including the ELS market.

The salience effect not only renders ELS products attractive but also prompts investors to choose a riskier ELS product. In the Allais Paradox experiment, participants are presented with two products: Product A offering a 34% chance of winning KRW 2.5 million, and Product B offering a 66% chance of winning nothing. When asked to select one product, the majority of participants opted for Product A. This result is contrary to the risk aversion typically exhibited by average individuals. In terms of the salience theory, it can be interpreted as the salience of the KRW 2.5 million reward in Product A leading participants to accept a low level of additional risk.5) The same principle applies to ELS investing, where investors may show a bias towards products offering higher coupon rates. This bias arises because the difference in coupon rates is the most prominent feature when different ELS products are compared, and the corresponding increase in risk, linked to higher coupon rates, is not as obvious. In particular, the higher the coupon rate offered by ELS products, the more complex their structure, which poses challenges for investors in recognizing the risk. As noted by Célérier & Vallée (2017), the salience effect led to a surge in the sale of products offering higher coupon rates during periods of low interest rates, which substantially heightened the complexity and risk of these products.

Biases in illiquid asset investment

Illiquid assets refer to tangible assets such as real estate, infrastructure, and commodities in the narrow sense. Broadly, they also encompass private equity funds such as hedge funds and PE. These assets have a number of advantages over their more liquid counterparts. First, their returns have a low correlation with traditional assets like stocks and bonds, thereby serving as effective diversification tools. Second, as market inefficiencies are more pronounced in illiquid assets, investors with expertise in a particular area are likely to have ample opportunities to achieve excess returns. In other words, leveraging illiquid assets as a diversification tool could mitigate the volatility of a conventional portfolio while boosting returns. Third, returns from real assets are often directly linked to inflation, making them a useful inflation hedge. Fourth, investing in illiquid assets enables large institutional investors to broaden investment opportunities. Pension funds, insurance companies, and other large institutional investors may face operational constraints due to their strong presence in traditional asset markets, some of which can be alleviated through investing in illiquid assets.

On the other hand, illiquid assets have the distinct drawback of being “illiquid”, as the name implies. These assets are not readily disposed of, potentially exposing investors holding them to liquidity risk in times of unfavorable market conditions. For instance, market demand for illiquid assets plunged during the 2008 global financial crisis, making it difficult to sell them. Even high-profile pension funds such as CalPERS, Havarad, and Yale experienced liquidity crises (Tédongap & Tafolong, 2018). In addition, illiquid asset trading involves higher costs, such as brokerage fees and taxes, and the transaction entails a complex structure, often requiring a considerable time to complete. Therefore, illiquid assets are suitable only for investors who are willing to make long-term investments and have sufficient liquidity.

Some scholars are concerned about the increasing investments in illiquid assets. They point out that the error of valuing illiquid assets in the same way as traditional assets can generate a bias toward overinvesting in illiquid assets. These assets typically do not have market prices and have long valuation cycles. Even their prices are often valued primarily based on previous data, resulting in smoothing returns. The smoothing of returns changes the statistical properties of illiquid assets, such as underestimating their return volatility and affecting their estimated correlation with other assets.6) Accordingly, statistical properties such as mean, variance, and correlation used for traditional assets should not be applied to illiquid assets. Underestimating the risk of illiquid assets may lead investors to overweight them in portfolios. This underscores the need to adjust the weight of illiquid assets in portfolios by imposing constraints or penalties on asset allocation.

Illiquid assets also introduce biases in performance evaluation. Specifically, the smoothing of illiquid asset returns alleviates the volatility of the entire portfolio’s performance. While the smoothing return effect can be partially controlled during asset allocation using the methods mentioned above, it is challenging to adjust for the effect during the ex-post evaluation of actual performance. Therefore, institutional investors with greater holdings of illiquid assets are more likely to exhibit less volatility in their performance. The stability in a fund’s performance serves as a critical indicator for the board of directors of long-term funds, such as pension funds, when evaluating performance ex post. For example, if a particular fund incurs relatively smaller losses during market downturns while other funds suffer considerable losses, there is a high likelihood of the fund manager being reappointed (Baz et al., 2022). For this reason, some fund managers may view investing in illiquid assets as a safe strategy (Asness, 2019. 12. 19) and prefer to invest in those assets.

Conclusion

The structured and illiquid asset markets have seen remarkable growth over the years. This is a positive development, as it has provided investors with a source of excess returns in exchange for sharing risk in new fields. However, structured and illiquid assets entail new types of risks that investors may not be familiar with, necessitating careful risk assessment before any investments are made. Investors without a thorough understanding of these risks can be exposed to various cognitive biases, including the ones mentioned above. This can lead to overinvesting in certain assets, which may cause significant difficulties if market conditions deteriorate.

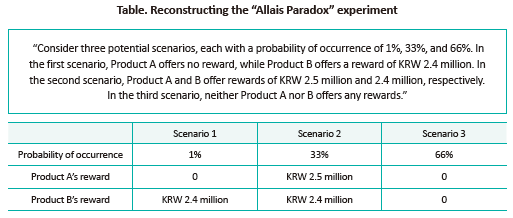

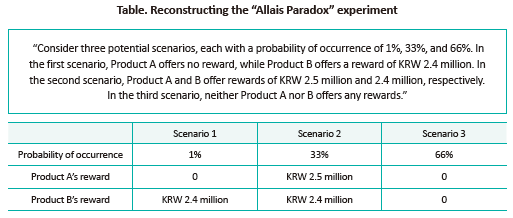

The government and the relevant industry should be careful not to overexpose investors to biases. According to Bordalo et al. (2012), when conditions in the Allais Paradox experiment were reconstructed as shown in the Table below, a majority of participants opted for Product B, showing no risk-seeking behavior unlike in the previous experiment. Since there was no difference in the absolute probability or reward between the two experiments, it is worth noting that information reconstructing can play a pivotal role in correcting investor biases.7) In this respect, the government and industry can gain insights from this experiment when devising relevant policies.

Investors need to acknowledge that they are susceptible to cognitive biases and take care to avoid them. The foremost, unchanging rule in investing is to “diversify your portfolios”. There is no such thing as a product that offers permanently high returns, which applies to those labeled “medium risk, medium return” in the previous low interest rate environment. All in all, it is of paramount importance to build a balanced portfolio that is not overly weighted toward particular assets. Even if a product offers a high coupon rate or appears to have a low risk of loss, it is essential to strictly limit its allocation within portfolios to ensure diversification.

1) The aggregate outstanding balance includes ELB and DLB.

2) Average investors in the derivatives market prefer to buy options, and conversely, avoid short positions. Therefore, investors who sell options can address the market imbalance in favor of buyers (market completion) and, in return, receive a premium.

3) The risk of the opposite position can also be fragmented and spread across many investors through financial instruments. However, that does not mean it completely disappears.

4) Technically, there are also risks stemming from price declines of underlying assets (delta risk), changes in price volatility (vega risk), the passage of time (theta risk), interest rate levels (rho risk), and correlations among underlying assets (Jung & Ahn, 2013).

5) In another experiment involving the same participants, Product A offers a 33% chance of winning KRW 2.5 million, a 66% chance of winning KRW 2.4 million, and a remaining 1% chance of winning nothing. Meanwhile, Product B offers a guaranteed KRW 2.4 million with a 100% probability. In this case, the majority of participants exhibited risk-aversion by choosing Product B. Compared to the first experiment, this second experiment merely adds a 66% probability of winning KRW 2.4 million to each product. Despite this similarity, the differing choices of the two experiments are paradoxical, and this difference has been of great interest of academics since this was first raised in 1953.

6) For example, Baz et al. (2022) pointed out that the return volatility of the Preqin index which represents the performance of buyout private equity funds, was excessively low. It has been estimated that if the value of the unlisted companies, of which shares are held by these funds, are assessed in the same manner as listed companies, the return volatility of the index would be approximately three times higher than it currently is.

7) According to Bordalo et al. (2012), participants in the new experiment perceived the “risk of not gaining KRW 2.4 million in the first scenario” as the most salient feature. The prominence of the KRW 2.5 million reward provided by Product A in the original experiment was significantly diluted by the alternative reward of KRW 2.4 million offered by Product B in the second scenario of the new experiment.

References

Asness, C., 2019. 12. 19, The illiquidity discount?, AQR Perspective.

Baz, J., Davis, J., Han, L., Stracke, C., 2022, The value of smoothing, The Journal of Portfolio Management 48(9), 73-85.

Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., Shleifer, A., 2012, Salience theory of choice under risk, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, 1243–1285.

Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., Shleifer, A., 2016, Competition for attention, The Review of Economic Studies 83, 481–513.

Célérier, C., Vallée, B., 2017, Catering to investors through security design: Headline rate and complexity, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132, 1469–1508.

Tédongap, R., Tafolong, E., 2018, Illiquidity and investment decisions: A survey, Amundi Research Center working paper 70-2017.

[Korean]

Kang, B.J., 2016, Investment efficiency of structured derivatives: Automatic early redemption ELS, Asian Review of Financial Research, 29, 77–112.

Jung, S.H. & Ahn, S.H., 2013, Study on investor production of ELS and DLS, Korean Academy of Financial Consumers, 3(1), 44-107.

Biases in structured asset investing: A focus on ELS

ELS, introduced in Korea in 2003, represents a typical structured asset class that drew significant attention as a “financial product innovation”. It has contributed to broadening investment choices for the general public. For example, step-down ELS involves a profit structure similar to that of selling a put option, providing investors with option premiums. These option premiums can be an attractive choice for investors seeking excess returns above market interest rates.2) Before the introduction of ELS, these option premiums were typically reserved for financial institutions. For investors to directly sell options from their accounts, they needed to maintain sufficient margin and satisfy regulatory requirements set by financial authorities or exchanges, as well as the strict trading conditions imposed by individual securities firms. In particular, the “deep out of the money option with maturities longer than six months”, included in step-down ELS, could only be traded as an over-the-counter product, making it accessible exclusively to financial institutions with adequate creditworthiness, despite its relatively low risk compared to typical put options. The emergence of ELS has addressed these limitations and expanded retail investors’ access to over-the-counter derivatives. In addition, despite the inclusion of derivatives, ELS has enhanced convenience for retail investors by limiting potential losses to 100% and allowing for small investments. Consequently, ELS has enabled retail investors with relatively low risk appetite, who may be hesitant to directly participate in the stock market, to benefit from investing in ELS while managing a relatively low level of market risk. In other words, ELS can be seen as a product that fulfills one of the fundamental functions of finance: “risk diversification”.

Despite these positive effects, ELS comes with its own drawback of complicating the understanding of inherent risks for ordinary investors. In the derivatives market, there is always an investor taking an opposite position, and selling a put option involves a transaction conducted in the opposite direction of put option buyers. The counterparty buying the put option would not pay for an event that has no possibility of occurring.3) Although ELS is considered to entail a relatively low level of risk, it inevitably carries risk to some extent. Furthermore, the risk associated with put options stands in stark contrast to the risk commonly faced by ordinary investors in the stock market. Specifically, while the frequency of losses in ELS is significantly lower than in stocks, the value of the expected loss is substantially large once it occurs (Kang, 2016).4) This risk is not readily recognized by ordinary investors, and as a result, they may opt for a product that hardly aligns with their risk appetite and suffer significant losses.

Investors are susceptible to cognitive biases as they struggle to fully grasp the risk inherent in ELS investing. For example, in the case of step-down ELS, investors can see the coupon or rate of return they can earn if certain conditions are met. In a low interest rate environment, the ELS coupon rate may be perceived as being significantly higher than market rates, which induces investors to overreact and recognize ELS as a more attractive investment than it really is. When the market rate stands at one percent, an ELS coupon rate of five percent may seem quite appealing. In this situation, investors tend to overestimate the prominent features of a financial product such as its coupon rate, while undervaluing less conspicuous features like the risk of loss. This tendency is well demonstrated by Bordalo et al. (2012, 2016) who elucidate this phenomenon by applying the “Salience Theory”. For this reason, investors show a propensity to allocate excessive investments in ELS products. According to Célérier & Vallée (2017), amid a low interest rate environment, this salience effect significantly contributed to the growth of the European structured asset market, including the ELS market.

The salience effect not only renders ELS products attractive but also prompts investors to choose a riskier ELS product. In the Allais Paradox experiment, participants are presented with two products: Product A offering a 34% chance of winning KRW 2.5 million, and Product B offering a 66% chance of winning nothing. When asked to select one product, the majority of participants opted for Product A. This result is contrary to the risk aversion typically exhibited by average individuals. In terms of the salience theory, it can be interpreted as the salience of the KRW 2.5 million reward in Product A leading participants to accept a low level of additional risk.5) The same principle applies to ELS investing, where investors may show a bias towards products offering higher coupon rates. This bias arises because the difference in coupon rates is the most prominent feature when different ELS products are compared, and the corresponding increase in risk, linked to higher coupon rates, is not as obvious. In particular, the higher the coupon rate offered by ELS products, the more complex their structure, which poses challenges for investors in recognizing the risk. As noted by Célérier & Vallée (2017), the salience effect led to a surge in the sale of products offering higher coupon rates during periods of low interest rates, which substantially heightened the complexity and risk of these products.

Biases in illiquid asset investment

Illiquid assets refer to tangible assets such as real estate, infrastructure, and commodities in the narrow sense. Broadly, they also encompass private equity funds such as hedge funds and PE. These assets have a number of advantages over their more liquid counterparts. First, their returns have a low correlation with traditional assets like stocks and bonds, thereby serving as effective diversification tools. Second, as market inefficiencies are more pronounced in illiquid assets, investors with expertise in a particular area are likely to have ample opportunities to achieve excess returns. In other words, leveraging illiquid assets as a diversification tool could mitigate the volatility of a conventional portfolio while boosting returns. Third, returns from real assets are often directly linked to inflation, making them a useful inflation hedge. Fourth, investing in illiquid assets enables large institutional investors to broaden investment opportunities. Pension funds, insurance companies, and other large institutional investors may face operational constraints due to their strong presence in traditional asset markets, some of which can be alleviated through investing in illiquid assets.

On the other hand, illiquid assets have the distinct drawback of being “illiquid”, as the name implies. These assets are not readily disposed of, potentially exposing investors holding them to liquidity risk in times of unfavorable market conditions. For instance, market demand for illiquid assets plunged during the 2008 global financial crisis, making it difficult to sell them. Even high-profile pension funds such as CalPERS, Havarad, and Yale experienced liquidity crises (Tédongap & Tafolong, 2018). In addition, illiquid asset trading involves higher costs, such as brokerage fees and taxes, and the transaction entails a complex structure, often requiring a considerable time to complete. Therefore, illiquid assets are suitable only for investors who are willing to make long-term investments and have sufficient liquidity.

Some scholars are concerned about the increasing investments in illiquid assets. They point out that the error of valuing illiquid assets in the same way as traditional assets can generate a bias toward overinvesting in illiquid assets. These assets typically do not have market prices and have long valuation cycles. Even their prices are often valued primarily based on previous data, resulting in smoothing returns. The smoothing of returns changes the statistical properties of illiquid assets, such as underestimating their return volatility and affecting their estimated correlation with other assets.6) Accordingly, statistical properties such as mean, variance, and correlation used for traditional assets should not be applied to illiquid assets. Underestimating the risk of illiquid assets may lead investors to overweight them in portfolios. This underscores the need to adjust the weight of illiquid assets in portfolios by imposing constraints or penalties on asset allocation.

Illiquid assets also introduce biases in performance evaluation. Specifically, the smoothing of illiquid asset returns alleviates the volatility of the entire portfolio’s performance. While the smoothing return effect can be partially controlled during asset allocation using the methods mentioned above, it is challenging to adjust for the effect during the ex-post evaluation of actual performance. Therefore, institutional investors with greater holdings of illiquid assets are more likely to exhibit less volatility in their performance. The stability in a fund’s performance serves as a critical indicator for the board of directors of long-term funds, such as pension funds, when evaluating performance ex post. For example, if a particular fund incurs relatively smaller losses during market downturns while other funds suffer considerable losses, there is a high likelihood of the fund manager being reappointed (Baz et al., 2022). For this reason, some fund managers may view investing in illiquid assets as a safe strategy (Asness, 2019. 12. 19) and prefer to invest in those assets.

Conclusion

The structured and illiquid asset markets have seen remarkable growth over the years. This is a positive development, as it has provided investors with a source of excess returns in exchange for sharing risk in new fields. However, structured and illiquid assets entail new types of risks that investors may not be familiar with, necessitating careful risk assessment before any investments are made. Investors without a thorough understanding of these risks can be exposed to various cognitive biases, including the ones mentioned above. This can lead to overinvesting in certain assets, which may cause significant difficulties if market conditions deteriorate.

The government and the relevant industry should be careful not to overexpose investors to biases. According to Bordalo et al. (2012), when conditions in the Allais Paradox experiment were reconstructed as shown in the Table below, a majority of participants opted for Product B, showing no risk-seeking behavior unlike in the previous experiment. Since there was no difference in the absolute probability or reward between the two experiments, it is worth noting that information reconstructing can play a pivotal role in correcting investor biases.7) In this respect, the government and industry can gain insights from this experiment when devising relevant policies.

1) The aggregate outstanding balance includes ELB and DLB.

2) Average investors in the derivatives market prefer to buy options, and conversely, avoid short positions. Therefore, investors who sell options can address the market imbalance in favor of buyers (market completion) and, in return, receive a premium.

3) The risk of the opposite position can also be fragmented and spread across many investors through financial instruments. However, that does not mean it completely disappears.

4) Technically, there are also risks stemming from price declines of underlying assets (delta risk), changes in price volatility (vega risk), the passage of time (theta risk), interest rate levels (rho risk), and correlations among underlying assets (Jung & Ahn, 2013).

5) In another experiment involving the same participants, Product A offers a 33% chance of winning KRW 2.5 million, a 66% chance of winning KRW 2.4 million, and a remaining 1% chance of winning nothing. Meanwhile, Product B offers a guaranteed KRW 2.4 million with a 100% probability. In this case, the majority of participants exhibited risk-aversion by choosing Product B. Compared to the first experiment, this second experiment merely adds a 66% probability of winning KRW 2.4 million to each product. Despite this similarity, the differing choices of the two experiments are paradoxical, and this difference has been of great interest of academics since this was first raised in 1953.

6) For example, Baz et al. (2022) pointed out that the return volatility of the Preqin index which represents the performance of buyout private equity funds, was excessively low. It has been estimated that if the value of the unlisted companies, of which shares are held by these funds, are assessed in the same manner as listed companies, the return volatility of the index would be approximately three times higher than it currently is.

7) According to Bordalo et al. (2012), participants in the new experiment perceived the “risk of not gaining KRW 2.4 million in the first scenario” as the most salient feature. The prominence of the KRW 2.5 million reward provided by Product A in the original experiment was significantly diluted by the alternative reward of KRW 2.4 million offered by Product B in the second scenario of the new experiment.

References

Asness, C., 2019. 12. 19, The illiquidity discount?, AQR Perspective.

Baz, J., Davis, J., Han, L., Stracke, C., 2022, The value of smoothing, The Journal of Portfolio Management 48(9), 73-85.

Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., Shleifer, A., 2012, Salience theory of choice under risk, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, 1243–1285.

Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., Shleifer, A., 2016, Competition for attention, The Review of Economic Studies 83, 481–513.

Célérier, C., Vallée, B., 2017, Catering to investors through security design: Headline rate and complexity, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132, 1469–1508.

Tédongap, R., Tafolong, E., 2018, Illiquidity and investment decisions: A survey, Amundi Research Center working paper 70-2017.

[Korean]

Kang, B.J., 2016, Investment efficiency of structured derivatives: Automatic early redemption ELS, Asian Review of Financial Research, 29, 77–112.

Jung, S.H. & Ahn, S.H., 2013, Study on investor production of ELS and DLS, Korean Academy of Financial Consumers, 3(1), 44-107.